“Please write about us!”, said Esperanza to me before we parted. “We don’t get many visitors. Maybe if someone reads about our village, they will come here”. More than a year after our visit to the tiny indigenous community of Los Ramos in Ometepe island, I still remember her words. It’s time I fulfilled the promise.

Los Ramos lies at the foothills of Concepción volcano. Coming here after 2 stunning days on the island, we were drawn by a community project offering homestay with local families.

The village was shrouded in darkness, when we arrived on a late evening. Our taxi driver went out with a flashlight to look for our hosting family. Voices coming from the dark guided us to the right house. The family greeted us and led us to the bedroom.

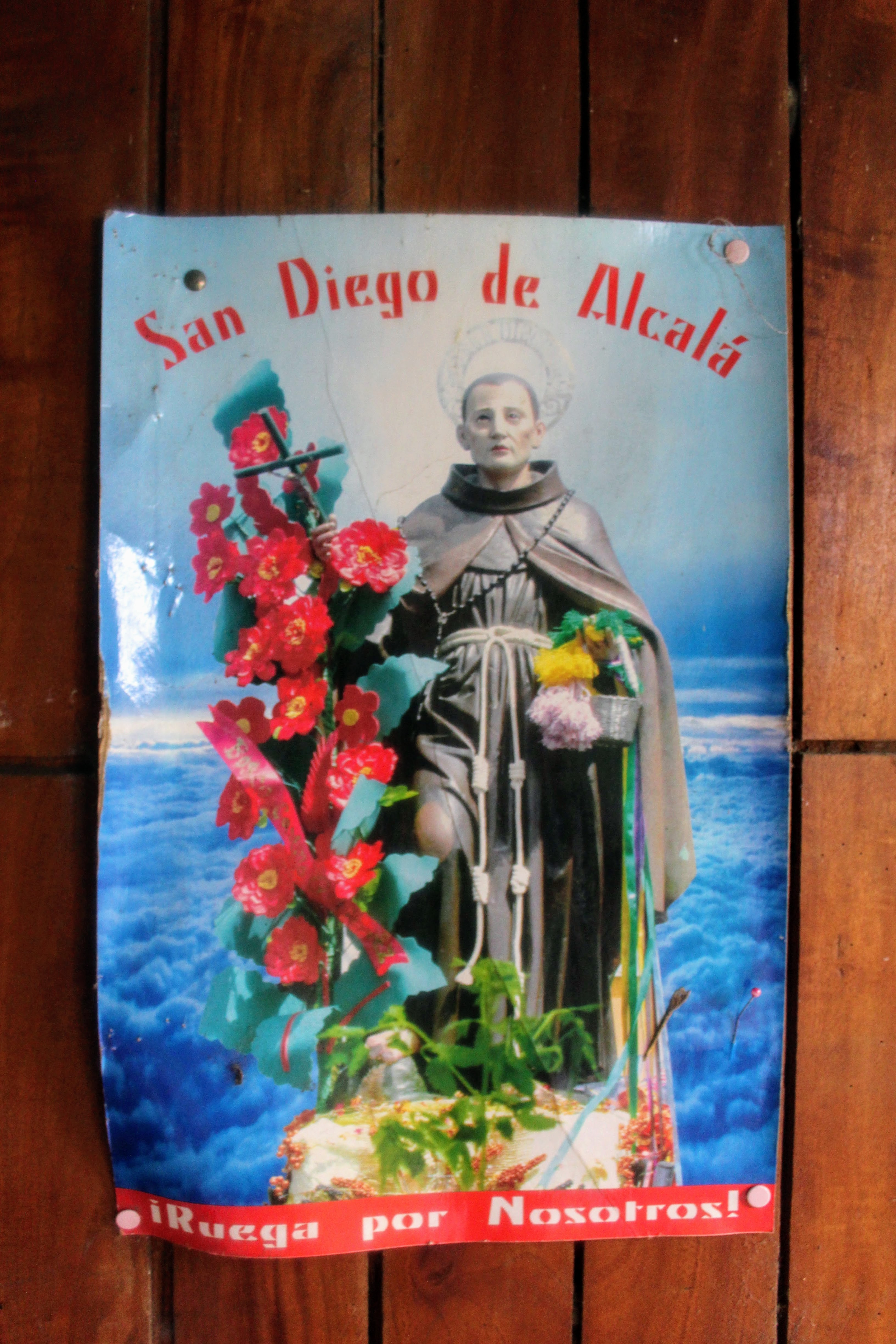

Shabby fibre cement roof, large cracks between the walls and the ceiling, mosquito bed nets, posters of the pope and a local saint. The room was neat but very simple. We would soon find out it was the most luxurious room in the house.

Next morning I found our hostess in the kitchen preparing our breakfast. Esperanza Aleman is an elegant middle-aged woman with a kind smile. Every time our 4-year-old would pass by, she would take her apron to lovingly clean up his hands and face.

She is a single mother raising a school-age daughter and taking care of her frail father. They live together with her sister’s family. Extended families living together are common in many parts of Latin America.

This stone tool for making tortillas was passed for generations in Esperanza’s family. Of course Ayan had to try it himself.

A traditional stone stove takes most of the kitchen.

Outside, Ayan was mesmerized by the family pig wandering around the yard. Jaire Junior was watching Ayan.

Jaire senior, junior’s father and the brother-in-law of Esperanza came out to greet us. Talking with enthusiasm about all aspects of their life in the village, it was clear Jaire and Esperanza understood well what visitors are interested in.

Crude brick walls not covered with paint. Common spaces laid with asphalt or dirt floors. Old broken toys lying on the floor. The striking poverty of the household was hard to ignore.

Houses in Los Ramos don’t have running water, so it has to be brought from a nearby village. The toilet has sewage, but flushing is done with a bucket of water.

Papaya trees growing around the house provide the family with fresh fruit. The family also grows some coffee, although not much.

To keep us occupied, Jaire took us on a tour of the family plantain growth.

Unlike bananas, plantains aren’t usually eaten raw because of the high starch content. In Central America they are commonly used in cooking and are treated more like vegetables than fruit.

Back at the house, the breakfast was ready. Papaya, plantains, bread, eggs. Not sophisticated, but fresh and made with love.

Sitting together in the dining room after breakfast, Esperanza was talking about the reality of living with an active volcano as a neighbour. “After the last eruption, the government has built a radio notification system for us. If we hear a signal, we run to the nearby hill. Two years ago a girl from our community was killed. Her name was Alexandra. Such a good girl”. Esperanza’s voice breaks.

That day the volcano succumbed to the constant rains, causing massive landslides around the island. The five-year-old Alexandra was on the slopes of the volcano with her parents who were taking care of their crops, when the landslide occurred.

Esperanza’s father came into the room, sat down and started singing and old local folk song. This elderly man wanted to contribute to the family effort to host us.

“We don’t get many visitors”, Esperanza told me then. “Maybe once a week someone comes to the village. And we are 8 families taking turns hosting visitors. I want to improve the house, but I need more money”. This was months before tourism in Nicaragua took a big hit due to the current political crisis.

After parting with Esperanza, we went with Jaire on a hike to the lake.

Following a path laden with ash and volcanic stones, he talked about Violeta Chamorro. The former president of Nicaragua, she brought peace to the country after the long years of Sandinista revolution and the Contra war. When I asked Jaire how comes levels of violent crime in Nicaragua are relatively low despite abundant poverty, he attributed it to the success of her weapon-buying campaign after the war, which helped eradicate the threat of continuing violence.

On the way we met villagers transporting plantains.

Soon we reached the coast. Across the bay, volcano Maderas was shrouded in clouds.

Here Jaire introduced us to Rogelio, a local fisherman, who took us on his boat to show his trade.

Time after time he would throw the fishing nets into the water, time and again they would return empty. In between, he would talk about his life on the island. He mentioned Alexandra, the girl killed in the landslide. “She was a happy child”, he said with his gaze fixed at the horizon. “Did you know her?”, I asked him. “I am her father”, he answered.

Rogelio has a 5-month baby boy now. Life goes on, but so does the pain.

When several little fish finally made an appearance, Rogelio collected the nets and began rowing back to the beach.

Nearby, locals were washing clothes and taking bath.

Rogelio’s wife prepared our lunch, which consisted of fried fish, rice, beans and tostones (fried green plantains). It was delicious, as only home food can be.

When Jaire junior took of his clothes and ran into the water, Ayan of course had to follow.

Soon both were submerged in water, enjoying the moment, as only four-year-olds can.

Back on the land, a mound of ash proved to be irresistible for aspiring volcano surfers.

Relaxing in a hammock, with my soul and body nourished, I was thinking how traveling in places like this offers a cure for the obnoxiously consumerist aspect of tourism. Staying in a homestay or buying something in a local market becomes almost a moral imperative. You know you contribute to the livelihoods of families that depend on it.

Soon a taxi would arrive to pick us up and take to Moyogalpa to board a ferry. Trying to hold on to a rare moment of contentment, I was wondering how a community that has so little, can give so much.