If an alien anthropologist would have landed on Earth and could visit only one city to learn about us, he would probably go to Mexico City. Walking its streets is traversing our story as humanity. The magnitude and scope of what it is here is breathtaking. So where do you start? You start by walking the Tacuba avenue – the oldest street in the city… and the entire continent.

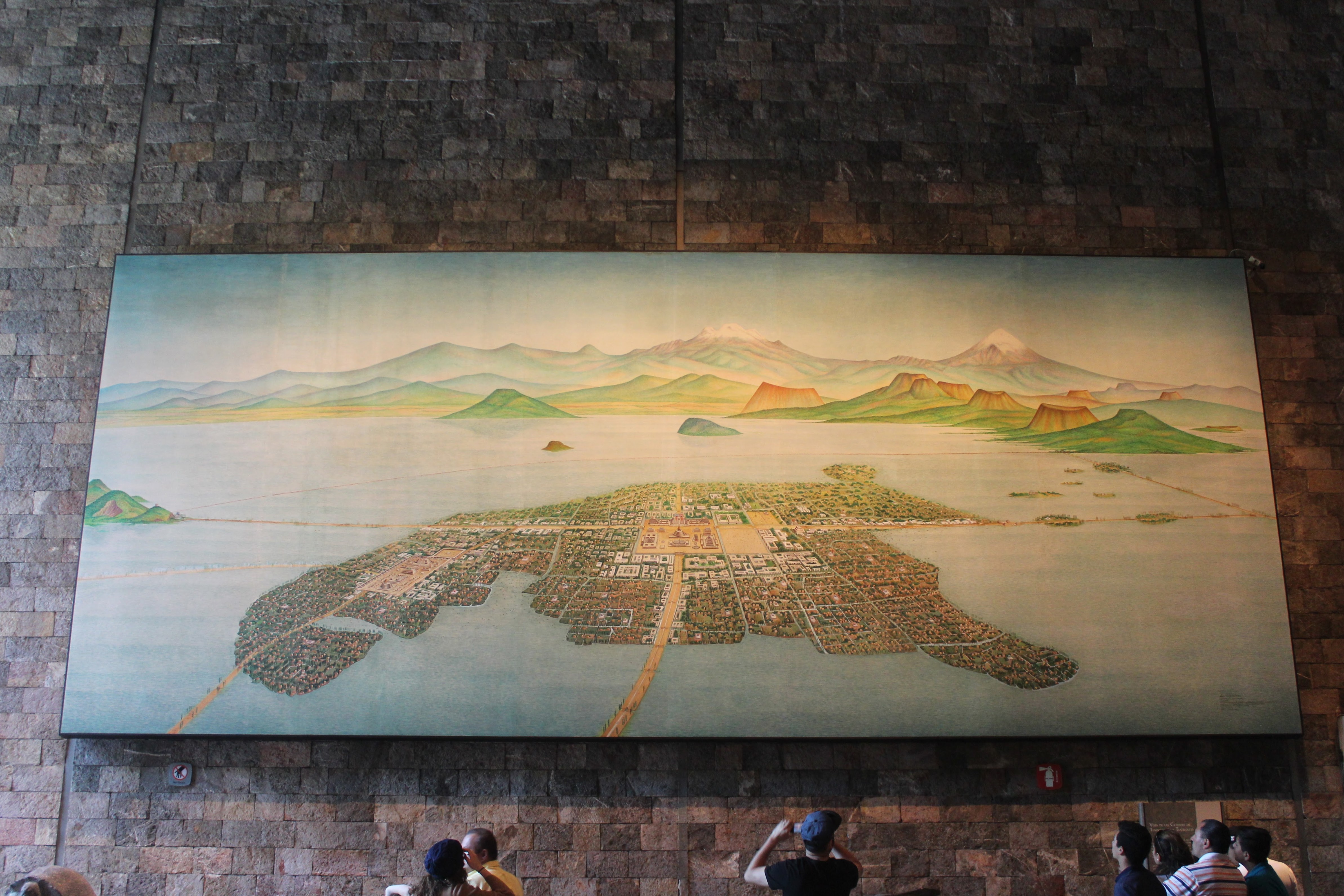

Tenochtitlán. That’s how Aztecs called their city. Founded in 1325, the city was built on an island in Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico. At its peak, it was the largest city in the Pre-Columbian Americas. Since then the lake has disappeared, drained and buried under modern Mexico City. But the road which connected the city with the western shores of the lake is still here.

The Mexico-Tacuba roadway is one of the four original roads that were built by the Mexicas whose main function was to connect Tenochtitlan with the settlements on the shore of the lake. You see the street crossing the city from top to bottom (that is from east to west), extending into the water and towards the viewer? That’s Calzada Tacuba. Right in the middle of it – that large square in the center of the map – was Templo Mayor, the main temple of the Aztecs. That’s where we’ll start our walk.

Contents

Templo Mayor

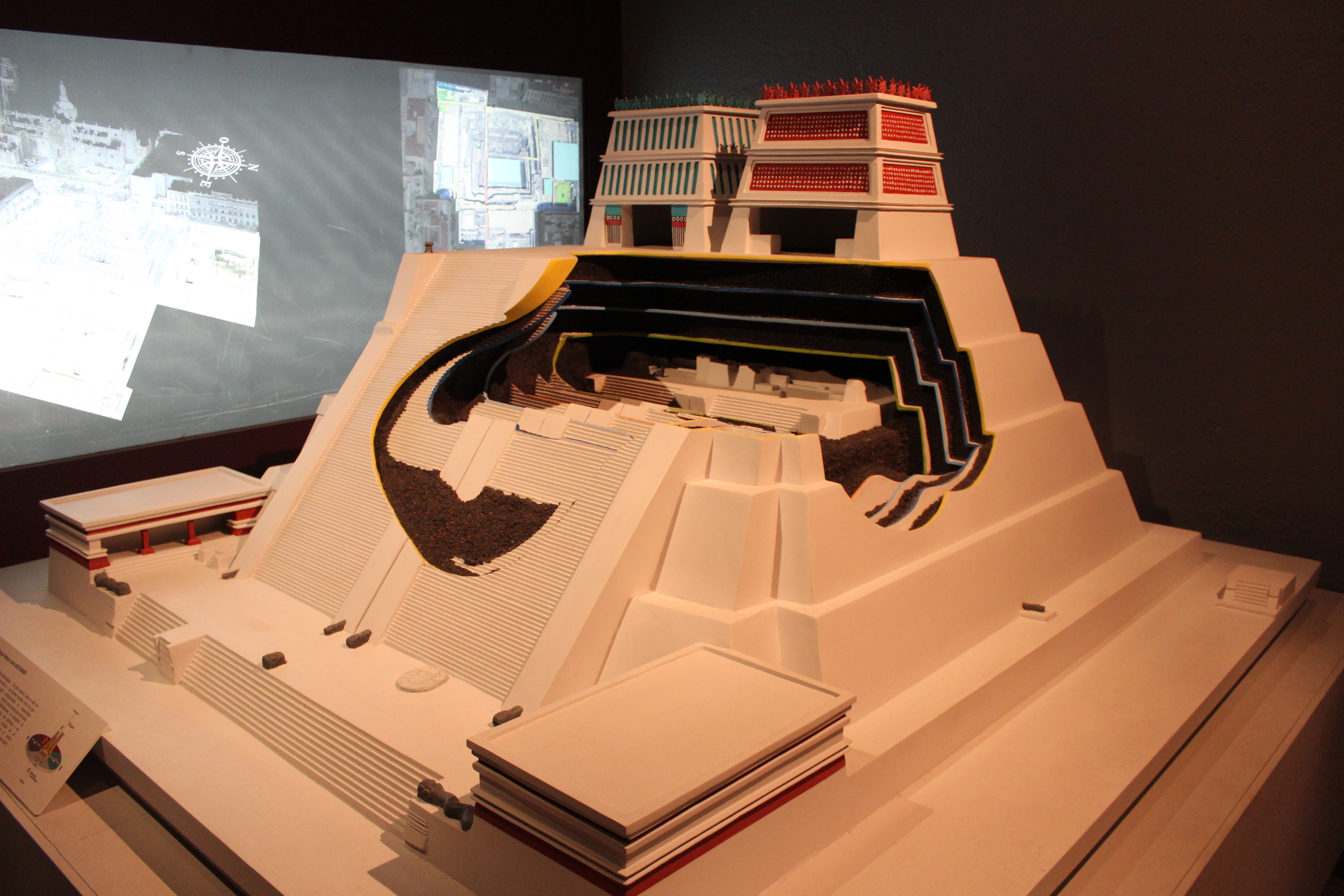

Imagine living your life and not knowing that right underneath your feet, in the center of your city, next to the main square, there is an ancient pyramid. Now imagine that it’s not one pyramid but actually seven, folded into each other like Russian babushkas. That’s the story of Templo Mayor.

After the destruction of Tenochtitlan by the Spanish, the Templo Mayor, like most of the rest of the city, was taken apart and covered over by the new Spanish colonial city. The Temple’s exact location was forgotten. Fast forward to 1978, when workers for the electric company were digging in a place called “island of the dogs” right next to Zocalo, the main square of Mexico City. Two meters below the surface they struck on a pre-Hispanic monolith. 4 years of excavations followed. 13 buildings in the area had to be demolished. 7000 artifacts were discovered. Slowly, Templo Mayor has reclaimed its place in center of the city.

Mexican pyramids were typically expanded by building over prior ones, using the bulk of the former as a base for the latter, as later rulers sought to expand the temple to reflect the growing greatness of the city. The first version of Templo Mayor was begun by the Aztecs the year after they founded the city. The pyramid was rebuilt six times.

The Templo Mayor pyramid was composed of four sloped terraces, topped by a great platform, with two shrines on the top of it (painted red and blue in the model). One was dedicated to Tlaloc, the god of rain on the left side, and one to Huitzilopochtli, deity of war and of the sun, on the right side.

On the sides of the Templo Mayor, there are a number of smaller palaces. One of the best preserved and most important is the Palace of the Eagle Warriors. The Eagle Warriors were a privileged class who were dedicated to the god Huitzilopochtli, and dressed to look like eagles.

After a tour of the temple and the surrounding structures, make sure to visit the museum. If only to see Tlaltecuhtli, the earth god.

The Last Viceroy of New Spain

Continuing our walk, from Templo Mayor we head west on Avenida República de Guatemala. That’s how Tacuba is called in this section. Over time, the sections that make up the avenue have changed names on more than one occasion. But they are still part of the same historic Tacuba avenue.

After crossing Calle Monte de Piedad the street changes its name to Tacuba proper.

Stores selling shoes, clothing, perfumes. The next three blocks are busy with commerce and trade, the bread and butter of city life.

Arriving at the corner with Isabel La Católica, there is an old building with a beautiful facade of volcanic stone. Here lived Doña Josefa Sánchez Barriga, wife of Juan de O’Donojú, who would be the last viceroy of New Spain.

Arriving to take office in July 1821, O’Donojú discovered that almost the entire colony supported the rebel general Agustín de Iturbide. O’Donojú used his influence to withdraw Spanish troops from the country with a minimum of bloodshed through reasonable surrender terms. In September he signed the Mexican Act of Independence. A month later he died, possibly poisoned by Iturbide.

His widow was promised a pension by the new Mexican republic, but in the chaos of those days, that promise never materialized. Unable to return to Spain, where her husband was considered a traitor, Doña lived for a few years in this house, slowly selling off everything she had. Eventually thrown on the street, she ended her days in poverty and hunger.

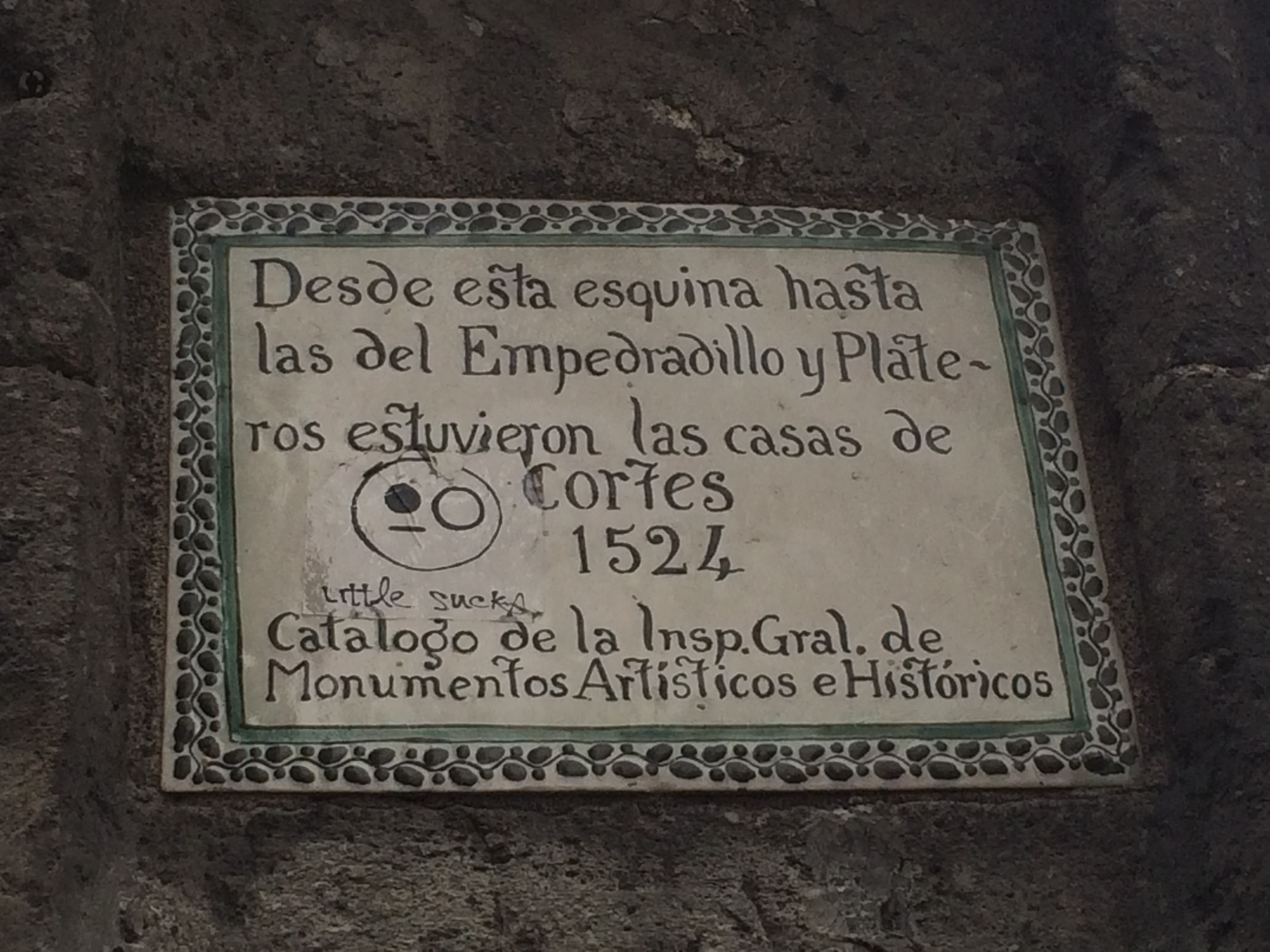

Cortés

The owner of the house she lived in was a descendant of Hernán Cortés. The plaque on the house confirms the connection:

But that’s not even the most interesting connection between Tacuba avenue and Cortes. One July night in 1520, following the death of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II, whom the Spanish had been holding hostage for a while, the invading army of Cortes left their compound and fled west, on Tacuba road. The Spaniards made their way out through the sleeping city under the cover of a rainstorm. But before reaching the causeway, they were noticed by the Eagle Warriors, who sounded the alarm.

In the ensuing fighting the Spanish suffered heavy casualties, but Cortes managed to escape. A year later he returned to finish the conquest. The night on Tacuba road was named La Noche Triste (“The Night of Sorrows”).

Cafe Tacuba

Walking another block and half we arrive at Cafe Tacuba, one of the oldest restaurants in Mexico City. Founded in 1921, it’s an institute of Mexican gastronomic traditions. But food isn’t the only reason we are here.

Rather it’s the place itself. Hanging on the walls are classical paintings from the Spanish colonial era.

In 1922, the muralist Diego Rivera married for second time, and the reception and banquet were held in the restaurant.

Two paintings from 1946 by Carlos González tell the story of the discovery of mole and chocolate.

Mosaics adorn the windows.

Walls and arches are decorated with intricate ornaments and tiles.

The employees here are serious and ceremonious, as should be expected.

The popular Mexican rock band Café Tacvba took their name in honor of the restaurant, when its members moved to Mexico City. The musical scene that developed around the restaurant in the 1940s and 1950s, was something the band acknowledged as an influence.

Their 1994 album “Re”, a wonderful mix of genres and styles, is a seminal album in the rock en español movement.

Palacio de Correos de Mexico

Another block from Cafe Tacuba, on the other side of the street stands Palacio de Correos, the spectacular headquarters of the Mexican post office.

Built in the beginning of the 20th century, it was designed by Italian architect Adamo Boari, who also designed the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

Its architectural style is highly eclectic, with the building being considered a mix of Art Nouveau, Spanish Renaissance Revival, Plateresque, Spanish Rococo style, Elizabethan Gothic among others.

Alameda Central

Across the street from the post office building, where Tacuba street becomes Avenida Hidalgo, stands the famous Palacio de Bellas Artes. It’s well worth a visit, but would require at least half-day on its own. Instead, we continue to Alameda Central, the oldest public park in the city and the continent.

Before becoming a park, the area used to be an Aztec marketplace.

Between vendors selling metal craftworks and tattoo artists at work, it still retains some of its original functions.

The park was created in 1529 by Viceroy Luis de Velasco, as part of a plan to develop what was, at that time, the western edge of the city.

During the Inquisition, witches were publicly burned here at the stake. The park was expanded in 1791, and a wooden fence was built around the park, to make it exclusive for the nobility. However, when Mexican Independence was won in 1821, Alameda was the center of popular celebrations.

At the far end of the park, Museo Mural Diego Rivera houses Rivera’s famous mural dedicated to the park, as the epicenter of Mexican history.

The mural was originally painted on a wall in hotel Prado, between 1946 and 1947. When the hotel was destroyed in the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, the mural was restored and moved to its own museum.

The mural represents the artist as a child walking in the Alameda Central accompanied by approximately 150 emblematic characters from 400 years of Mexican history.

In the far left fragment of the mural, victims of the Inquisition are consigned to the flames. In the bottom-left corner, we can see Hernan Cortes, with the goatee and the ruff collar. In the top-right corner, holding a manuscript is Benito Juárez, the first indigenous Mexican president.

On the right-side the mural depicts the conditions leading to the Mexican Revolution. The indigenous people are pushed aside from the park (and the society). The woman in the yellow dress confronting the elegant gentlemen is La Malinche, a Nahua woman who played a role in the Spanish conquest, acting as an interpreter, advisor and mistress of Cortes. She gave birth to his first son, who is considered to be one of the first Mestizos.

High above the scene stands Porfirio Diaz, a dictator whose 35-years rule of civil repression and political stagnation led to the outbreak of the revolution. His economic policies largely benefited his circle of allies and helped a few wealthy estate owners acquire huge areas of land, leaving rural campesinos unable to make a living.

The center of the mural is dominated by the elegantly dressed skeleton La Calavera Catrina, which satirically portraits the complacent and oblivious Mexican bourgeois, who were aspiring to adopt European aristocratic traditions in the pre-revolution era. La Catrina wears a feathered serpent boa around her shoulders, alluding to Quetzalcóatl, the feathered serpent god of the Aztec pantheon. She is holding hands with a child version of Diego Rivera in short pants. Rivera’s wife Frida Kahlo is standing just behind him.

If you arrive here during one of the many cultural events that are often held in the hall in front of the mural, you won’t be able to explore it up close. But when we were there, we were compensated with this sensual flamenco dance:

Outside the museum, Plaza de La Solidaridad is a small public square commemorating the victims of the 1985 earthquake. Here Sunday takes its slow course. Men play chess.

People of all ages dance salsa. The city that remembers so much, lives in the moment.

Tacuba avenue continues much further, under an array of changing names, but our walk comes to an end here. From the main temple of Tenochtitlán to Rivera’s mural salvaged from the 1985 earthquake, Tacuba has led us through the city’s story of conquest and destruction. Of revival and endless regeneration. This isn’t just the story of Mexico City. This is our story as humanity.

Thanks for the walk. You get better and better. The real magic is that with any luck a traveler can take a similar stroll through one of the world’s most exciting cities and layer those centuries of history with personal memories of great meals, personal encounters, live art. You’ve made that magic apparent.

Thank you Tom for the kind words 🙂

I completely agree with your statement – Mexico City is indeed one of the most exciting cities in the world, surely on the American continent. A city whose connection to its pre-hispanic past completely debunks the notion of “New World”

Thank you for this lively and beautiful article about my native city. Did you visit the Palacio Nacional? It’s like the Palacio de Bellas de Artes, it would probably take half a day to see it.

Hi Fabiola,

Thank you for your kind words, I’m glad you enjoyed the post.

Unfortunately, we haven’t had the chance to visit Palacio Nacional. We’ve been in the area a few times, but there was always a long line. Next time we are in the city, will make it a priority to get there ))

Do you currently live in Mexico City?

Just wonderful !! Thank you Mike !

Thank you Gordon!

Have you been to Mexico City?

Mike, this is a great travelogue. I have been to Mexico city, but before the uncovering of the Templo Mayor, so that part is fascinating to me.

Thank you Becky!

Templo Mayor is an unbelievable site. Have you been to Tlatelolco? Another grandiose Aztec temple, in the middle of a regular Mexico-City neighbourhood.

Wow. What a great post. I will go to México City next summer so I am reading every blog I find about it and you really madre me feel I was already there watching everything with my own eyes. What a great walk! When you know its history it really changes the way you see it and you make it so much fun and interesting! Thanks for your post!

Thank you Patricia, glad you enjoyed this post!

Great blog! I really, really appreciate that you took the time to see my photo and credit me!! All the best!! J. Makali Bruton

Thank you for the photo, it was indispensable for this travelog 🙂

This is a really beautiful post. I learned a lot about the downtown of Mexico City. I’ve been a few times but want to go again because of this post.

The only criticism is that you don’t show the hundreds of beggars or mention the rumors of theft and drug use in this area of the city. It’s a sad truth but as a journalist (of sorts?) maybe it’s important to include these populations, even in the slightest way since it isn’t the angle your post is taking. Anyway, that’s all 🙂

Thank you Ana,

Glad you enjoyed it (and sorry for getting back late).

Regarding the beggars, and some other issues you have mentioned – I haven’t noticed anything out of the ordinary walking the street. Unfortunately, poverty exists in the city almost everywhere you go. It’s worth talking about it, but as you pointed yourself, it wasn’t the point of the article.