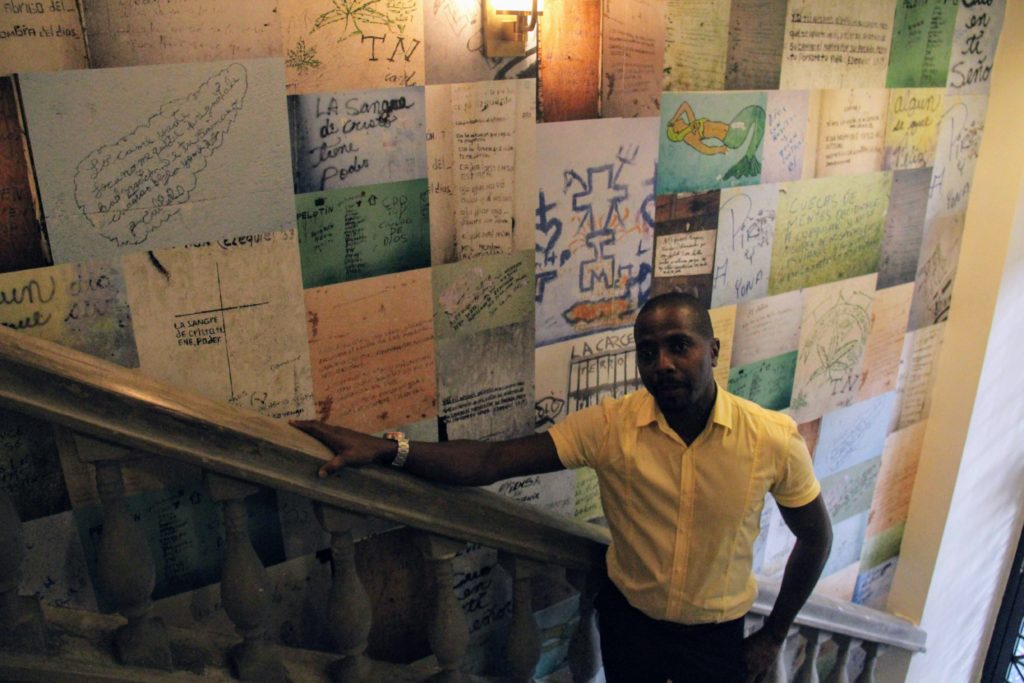

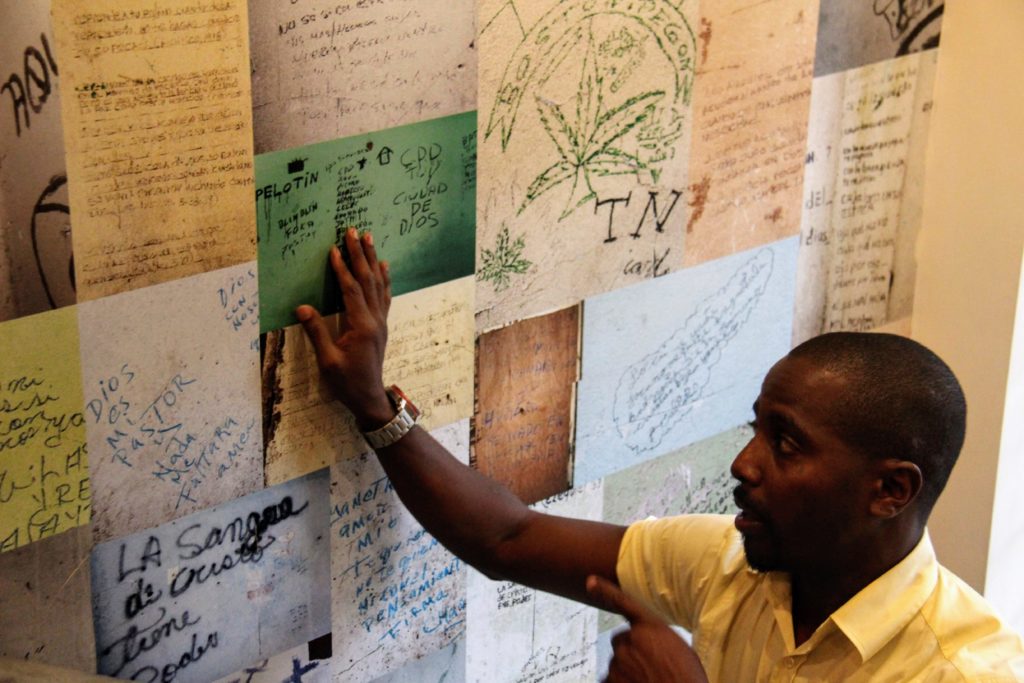

“I started working when I was 9 – selling flowers, mangoes on the street. By the time I was 14, I joined a gang”. Jafet Glissant, a smartly-dressed black man in his thirties, he stands on the stairs of the American Trade hotel. The walls of the hallway are covered with photos of how the place looked like just ten years ago. Today a luxury hotel, this used to be an abandoned colonial building controlled by the “Ciudad de Dios” gang. Called after the favela in the namesake Brazilian movie, it was one of the largest gangs operating in Casco Viejo and El Chorillo, the two sides of Panama City’s historical center.

“From this building we would take off, and here we would bring our spoils. Cameras, watches cash. Robbing tourists was our main line of work”.

“I grew up with four brothers and sisters. My mom, a single parent, was too busy making sure we have food and a roof over our heads, to be able to monitor us. I lacked a positive example in my life, so joining a gang was a natural thing”.

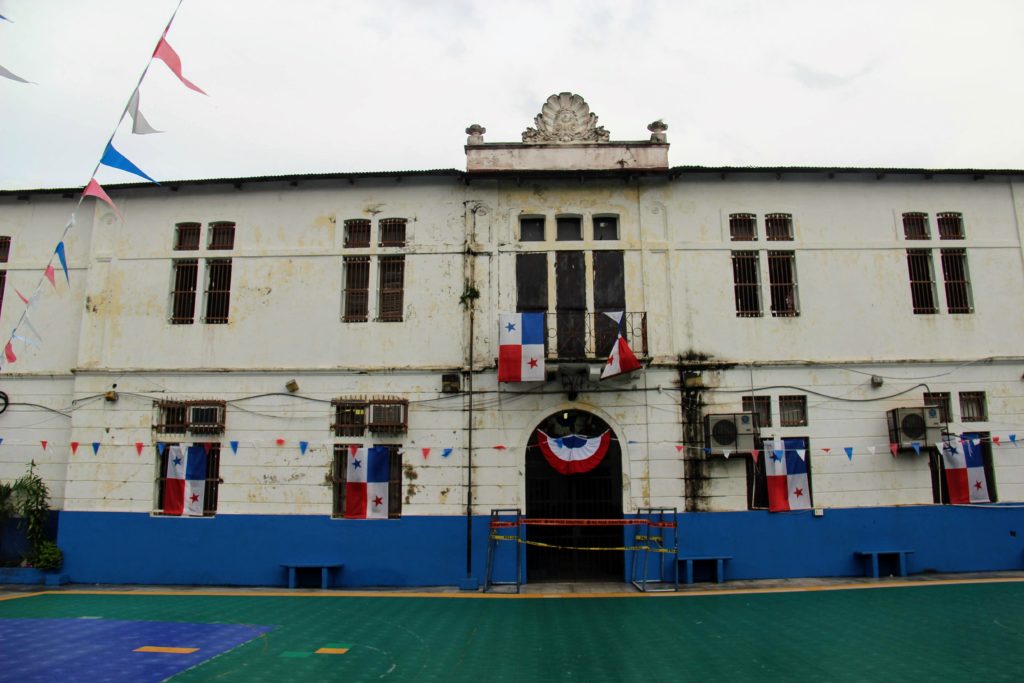

It all changed for Jafet thanks to one man: KC Hardin, an American investor who bought several buildings in Casco Viejo around 2004. At the time, more than 80 percent of the buildings in the quarter were unrestored, gangs controlled the district, and raw sewage leaked onto the streets. In order to resolve the gang tensions, his company invested heavily in a program to integrate gang members into the broader community.

“I was one of twenty six men participating in the Esperanza program. Today I’m in my 4th year of a law degree”, Jafet says proudly. Together with 4 other ex-gang members, he started the Fortaleza Tours company, to show tourists a side of the city they would be otherwise unaware of.

We leave the hotel, cross Plaza Herrera and start our walk on Calle 10 Oeste, which until recently was known as Zona robba (“the robbery zone”).

Turning to Calle Victoriano Lorenzo, we follow a narrow street called after one of the heroes of the Thousand Days civil war. Street art depicting Lorenzo’s legacy fills a long stretch of a wall.

Following high walls topped with barbed-wire, we are the gate of a local school. As the rest of the city, the school is decorated with Panamanian flags. November is “mes de fiestas patrias”, an entire month filled with patriotic dates.

One of the goals of the project started by KC Hardin was to limit the dislocation of locals, which often happens in the process of gentrification, among others by helping people purchase the apartments they live in.

The government, while slow to act, has managed to built several social housing projects for locals forced out of their homes.

Almost everyone we pass on the streets know and greet Jafet. The glances we get are friendly and curious.

The local public gym serves the whole community. One woman is boxing with a coach, another is running on the treadmill.

Portrait of Panamanian boxer Roberto Durán hangs on the wall. National hero in Panama, this is where he started.

El Chorrillo was founded in 1915, when immigrants started settling down in the area to work on the construction of the Panama Canal. Located on the water’s edge, it’s not far from the entrance to the canal. The nearby Panama Canal Zone, an unincorporated US territory until recently, used to be off limits for locals.

Continuing along Calle 20 de Diciembre, the grit of El Chorillo becomes more pronounced. Blocks of high-rise buildings in dire need of renovation fill up one side of the street.

On the other side, shanty houses reveal a side of Panama City unknown to most visitors.

Passing the crumbling sheds which house entire families, it’s easy to forget that just minutes away from here, the financial hub of Americas is buzzing with activity and money.

During the 1989 American invasion in Panama, El Chorrillo, was caught in the cross-fire. From midnight to dawn of Dec. 20, 1989, American troops stormed through El Chorrillo in search of Panamanian dictator Gen. Manuel Antonio Noriega. Rockets aimed at Noriega’s nearby military headquarters set fire to some houses. The general’s men, unhappy that the barrio did not back their ruler, set fire to others.

Hundreds of residents were killed, but a definitive list of the victims was never produced. The Invasion, an excellent Panamanian documentary about the memory of the American invasion, paints a picture of a society that has preferred to leave what has happened behind, but the individual memories and pain lingers.

I ask Jafet what he remembers of those days. “It was chaos, fire, looting, bodies on the streets. A complete collapse of the social order”. “Do you feel the society was able to rebuild itself since then”, I ask him. “It’s a process we are still very much living though”.

We turn right to Calle 19 Oeste, moving away form the ocean coast hidden from view by the high-rise buildings.

Parque de Los Aburridos (“Park of the bored”), is the center of social life of the community.

Bellow an old tree bursting through the roof, men are playing domino, talking the day’s events.

A house with a huge hat on its roof is known here, predictably, as El Sombrero.

Turning right to Calle B, we start making our way back to Casco Viejo. Running along the neighboring corregimiento of Santa Ana, the abandoned colonial houses here are a reminder of how most of Casco Viejo looked like just ten years ago.

“I do these tours to show tourists there is a world apart, just a street away from the fancy hotels and bars, to make this place visible. But it’s also important to me that people here in Chorillo can feel more connected to the outside world”, Jafet tells me.

“Casco Viejo opened to the world 5 years ago. Just 2 years ago you couldn’t walk safely here in Chorillo. Things change, slowly. A part of what we make from these walks, we invest back into the community”.

The doors of a local sastreria are open, inside a tailor is fitting a pair of jeans. The cat on the desk is too busy to give me a glance.

Two buildings sharing a wall. One – restored, hosting a boutique store. The other – abandoned after a fire. If there is a clear border between the poverty-stricken El Chorillo and the tourist-friendly Casco Viejo, it’s here.

Leaving El Chorillo behind, we are now firmly in the picture-perfect Casco Viejo.

Back in the hotel from which we started the tour, Jafet shows us pictures of his 6-year-old twin daughters. They attend a private school nearby. We part with Jafet and spend the rest of the evening in a tourist bubble – a rooftop bar, then Uber to our hotel. But it’s El Chorillo that we’ll remember.

4gr7yk